A case of double standards?

(This object hangs in the anteroom of the grand staircase. The exhibition then continues in the small room to the right)

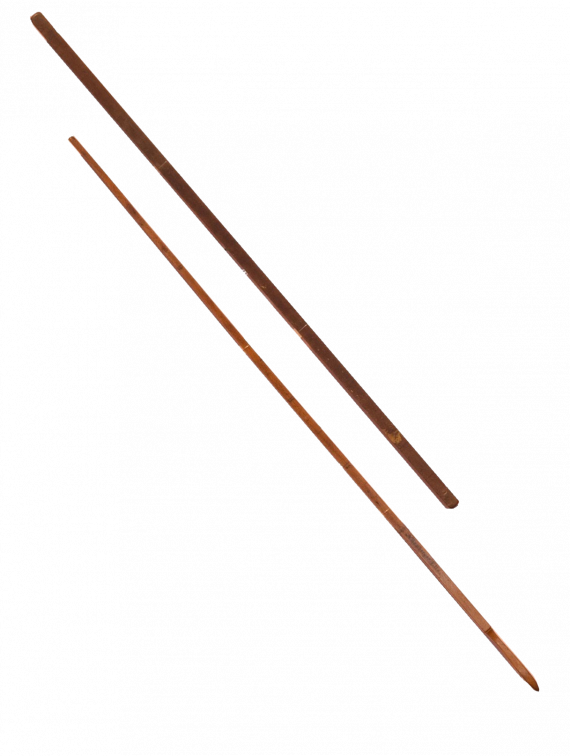

Until 1st October 1811, two sets of measurement units were in use in the Kingdom of Bavaria. It was only from this date that the units of measurement customary in the rest of Bavaria also began to apply in Erlangen. Until then, Nuremberg units had been used instead, although both the Old and New Towns of Erlangen had already become part of Bavaria in July 1810.

The most common unit of length at the time was the Elle (ell). It now corresponded to just over 83 cm, while previously it had been equivalent to just under 66 cm. Units of liquid and solid capacity were also affected by this change. Concurrent with the new units of measurement, Bavarian tax categories were also introduced. This standardisation represented an enormous simplification for tradespeople and the intra-Bavarian goods trade. However, the diversity of weights and measures in the German territories only ended with the founding of the German Empire in 1871. From then on, the meter served as the basis for all length measurements. Bavaria completed this conversion on 1st January 1872.

Bavarian ell

Wood

Length: 83 cm

before 1872

Nuremberg ell

Wood

Length: 66 cm (without handle)

ca. 1810

Medical Valley's germ cell?

In the 18th century, medical studies in Erlangen were predominantly theoretical in nature – there was no facility for practical 'bedside' training. In 1779, the physician Friedrich Wendt laid the first foundation stone for a university hospital. In his apartments, he set up a teaching and healing centre for the outpatient care of patients, the Collegium clinicum (known as Institutum clinicum from 1780).

However, the construction of a hospital initiated by Wendt did not progress as financial resources were lacking in the politically turbulent Napoleonic era. It was not until 1815 that the physician Bernhard Schreger was able to open a surgical Clinicum in today's Wasserturmstraße, where inpatient cases were also treated. The eight beds of this clinic represent the nucleus of today's university hospital, which with over 1300 beds and numerous research facilities is an important building block of Franconia's 'Medical Valley'.

Banner of the Department of Medicine

Linen with gold trim

1843

In addition to the departments of Philosophy, Theology and Law, the Department of Medicine is one of Erlangen University's four founding departments. On this banner created for the 100th anniversary of the founding of the university in 1843, it is symbolised by the ancient Greek goddess of healing, Hygieia. Her symbol, an Aesculapian snake drinking from a bowl, can still be found today as part of the emblem used by German pharmacies.

Did all roads lead to Erlangen?

It might seem like it – considering the four strands of traffic infrastructure that ran close to each other to the north of the Burgberg until the middle of the 20th century. This picturesque setting remained a popular motif until the construction of the Frankenschnellweg (Franconia Fast Link) motorway.

Joining two tried and tested transport routes – the highway and the Regnitz river – were, around 1845, two 'modern' ones, namely the Ludwig-Danube-Main-Canal and the railway. The latter surpassed the other three not only in terms of speed; the tunnel from which the tracks emerge was also the first of its kind in Bavaria.

The electrification of the Nuremberg-Saalfeld line in 1936 required an extension of the structure in both width and height, which somewhat diminished the originally well-proportioned design. The tunnel construction company was nevertheless proud of its achievement. It not only donated this commemorative stone, it also threw a celebration in honour of St. Barbara, the patron saint of miners, with an extensive programme of festivities and banquet.

Memorial stone for the extension of the Burgberg tunnel

Sandstone in metal setting

1936

The metal frame for this memorial stone shows both the northern and southern entrances to the Burgberg (Castle Hill) tunnel – the latter is shown after the widening carried out in 1936. An imperial eagle is emblazoned on the keystone.

Erlangen's breweries – a worldwide success story?

In the 19th century, Erlangen became a world-renowned 'beer town'. Cool rock cellars and rich sources of raw ingredients encouraged the brewing and storage of high-quality beer varieties. Connection to the railway network in 1844 promoted the export trade: At times, Erlangen exported more beer than Munich. European countries and even North America were supplied. The author Karl May also took note of this: In one of his fictional travel accounts, he has an Ottoman landlord rave about a legendary beer country named 'Elanka'. Erlangen had become synonymous with brewing culture.

However, most of the 18 breweries that existed around 1900 were of regional significance only. Due to the development of industrial cooling, Erlangen finally lost the site advantage of its natural cellars, and the number of its breweries shrank to four in the 20th century: Erich, Henninger, Kitzmann and Steinbach. Erlangen, however, continues to capitalise on its image as a beer town – not least thanks to the Bergkirchweih festival.

Beer bottles 'Erlanger Classic 1893' / 'Erlanger Märzen Bier'

Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company, Milwaukee / Stroh Brewery Company, Detroit

ca. 1979

The reputation of beers brewed in Erlangen reached as far as the USA. From 1893, the Schlitz brewery marketed not only beers called Pilsener and Budweiser, but also one called Erlanger. In 1979, the brand was relaunched for a few years – as a premium beer brewed according to the Bavarian Reinheitsgebot (Statute of Purity).

Karl May

In den Schluchten des Balkan (In the Balkan's Gorges)

ca. 1900

Karl May's mostly fictional travel accounts were bestsellers. The author stylised the 'orient' as an exotic staging ground for wild adventures, picking up on common clichés and stereotypes.

Anything else with that?

Words to that effect may have been used by grocer Friedrich Schmidt to address his customers in the middle of the 19th century. His shop offered 'Spezereien' (groceries), which at the time meant food items – mainly dry goods – and especially spices. The shop would certainly already have offered coffee, tea, cocoa and similarly 'exotic' commodities as well, which had been common since the 18th century, and soon became affordable for more and more people. Later, the term Kolonialwaren (colonial goods) prevailed for such products.

With this colossal carving, whose anchor motif refers to the maritime trade, shopkeeper Schmidt probably intended to draw attention to the origins of his wares in distant lands. It is notable that here, a dark-skinned man and a European-looking man sit opposite each other in harmony. The indigenous person is not yet characterised here as a member of an inferior species, which become customary later, but as a 'noble savage' with feathered headdress and gold cuffs. The reality of slave labour, on which the extraction of 'colonial goods' was based, is completely ignored in this depiction.

Shop sign for Schmidt's grocery

Wood

after 1841

Why are there neither dugongs nor manatees in Erlangen?

When the Sekundärbahn (secondary railway), jokingly referred to as Seku in the vernacular (sounding exactly like the German word 'Seekuh', meaning sea cow, the common name for the marine mammals dugong and manatee, and hinting at the train’s near cylindrical shape and sedate pace of locomotion), rattled through Erlangen for the last time on 17th February 1963, almost no one regretted its demise. Celebrated as a breakthrough to modernity for the villages in the Schwabach river basin when it opened in 1886, it was by now considered an obstacle to the flow of traffic. On a large part of the route between Erlangen and Eschenau, the tracks ran within the streets, and often through the centres of tightly built-up villages. As car traffic increased, accidents became more frequent. In the end, the Seku was limited to a maximum speed of 15 km/h, and required to stop at every give-way sign. It was no longer up to competing with motorised traffic, and eventually replaced by buses.

However, by the 1980s at the latest, long traffic jams and increasing environmental awareness pointed again to the advantages of rail transport. With the currently planned Stadt-Umland-Bahn (urban and surrounds railway), the idea of a 'secondary' railway has in part been revived.

Model of Erlangen's Zollhausbahnhof (Customs House Station)

Paper and card; Model maker: Friedemann Brandes

Scale 1:87

around 2008

Trix train set Deutsche Bahn (DB) branch line train 'Seku'

Scale 1:87