Entering the Industrial Age

Erlangen around 1830

Around 1830, on the cusp of the industrial revolution, Erlangen had ca. 9,800 inhabitants. It was the fourth largest town in Middle Franconia, and the tenth largest in Bavaria, which it had been part of since 1810. Its sense of pride was vested in its university, where 424 students were enrolled at the time. Contemporary images show the town surrounded by fields, still encircled by customs walls, and towered over by three church steeples marking its skyline.

Yet this smokescreen of a Biedermeier-style bourgeois idyll obscured economic stagnation and poverty. The once flourishing manufacturing workshops of the hatters and cotton printers had vanished, and hosiery manufacture – the town's main industry during the 18th century – had become backward and entered its decline. Even state support was barely able to alleviate the woes of the remaining 300 or so master hosiers. Of the old Huguenot exporting trades, glovemaking alone succeeded in adapting to the conditions prevailing at the time.

The town itself was poor and deeply in debt, its influence limited. Only few streets and squares were paved; sewage disposal was by way of the gutters. Like everywhere else, the inhabitants still obtained their drinking water from public and private wells. The dim glow of oil lamps provided the only public lighting.

Goods were transported in carts, many of which passed Erlangen on the busy highway connecting Nuremberg and Bamberg. The only form of public transportation was the mail coach. Passenger fares were so steep, however, that ordinary people travelled on foot. It took around four hours to journey to Nuremberg, which is where construction of the first German railway was in its planning stage at the time.

The canal

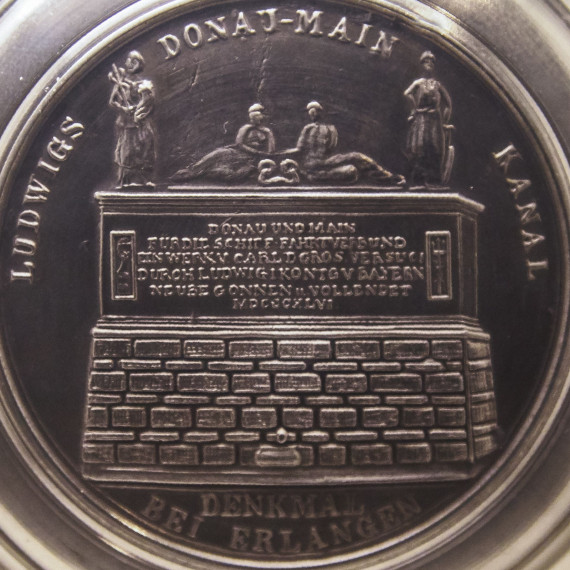

The idea of connecting the rivers Main and Danube with an artificial waterway can be traced back to Charlemagne, and had been under consideration repeatedly since the 17th century. This ambitious project wasn't realised, however, until the reign of Ludwig I – at a time when railway construction had already begun.

In 1836, under a royal warrant from the Bavarian king, and with the state as stakeholder, a public company was founded for the construction of the canal, and earthworks commenced the same year. In 1845, the Ludwig-Donau-Main-Kanal ('Ludwig-Danube-Main-Canal') was completed between Kelheim and Bamberg. At ca. 17.4 million guilders, construction costs rose to more than double the original estimate. The shortfall was covered by the state, who in 1852 became its sole proprietor.

As an infrastructure policy measure, the Ludwigs-Kanal ('Ludwig Canal') soon turned out to be a failed investment. The volume of goods transported had already peaked after five years, only to decline steadily thereafter. Over the long term, the canal was unable to compete with the railways.

Still, the Ludwigs-Kanal was more than an anachronism. It was also an expression of a zeitgeist oriented towards progress that gambled on overcoming natural obstacles with technological marvels.

The railway

In Germany, the railway age began with the Ludwigsbahn ('Ludwig Line') opened in 1835 between Nuremberg and Fürth. Modeled on this private train service, railway construction was initially promoted in Bavaria by public companies of shareholders. The concept of a state-owned railway only became established around 1840 with the construction of the first Bavarian long-distance railway, the Ludwigs-Süd-Nordbahn ('Ludwig South-North Line'). With the exception of the privately owned Ostbahn ('Eastern Line'), further development of the Bavarian rail network was now undertaken under the auspices of the state.

The railways gave industry a decisive push. With its capacity to transport large volumes, it opened new markets for raw materials as well as for finished goods, and secured the supply of consumer goods to the growing cities. Their demand for rails, locomotives, and rolling stock led to a rapid boom for the iron-producing and metalworking industries.

But Erlangen's economy lacked the conditions necessary to become a supplier of the railways. The town's early connection to the rail network, however, brought great advantages. Erlangen was situated along the Ludwigs-Süd-Nordbahn (Ludwig South-North Line), whose first section was opened between Nuremberg and Bamberg in 1844. The further expansion of this line meant that a continuous railway connecting Munich with Berlin via Nuremberg, Hof, and Leipzig could commence operations in 1851. Being connected to the railway network enabled an upswing for Erlangen's breweries, and created favourable conditions for the establishment of new enterprises such as the cotton mill.

< Previous chapter | Next chapter >