The Fischer mirror factory

This mirror and foil factory founded in 1744 was one of the few 18th-century enterprises in Erlangen that succeeded in jumping on the bandwagon of the industrial revolution. It was originally part of a commercial site consisting of five water wheels and hammer mills that used the hydrokinetic power provided by the river Regnitz.

The mirror factory had already been using mechanised devices for the grinding and polishing of the glass in the 18th century, while silvering was still done by hand. The foil factory manufactured the tin foil needed for mercury silvering, and operated several water-driven foil hammers.

In the first half of the 19th century, the company experienced a glorious rise under the direction of Johann Zephanias Fischer. After expanding the Erlangen factory and establishing several branches, it had become a leading representative of its sector by around 1840. Being Erlangen's largest enterprise at the time, it employed a total of 500 workers, over 100 of them in the town itself.

In 1859, the firm was converted into a public company in order to raise the capital needed to construct a modern glass factory in Zwickau. While this ambitious project remained unsuccessful, the company was, also in 1859, the first in Bavaria to successfully introduce actual silver into the silvering process.

This method becoming the dominant technology after 1889, however, led to the demise of tin foil manufacture, and consequently to a company crisis that precipitated its ultimate decline.

Mercury silvering

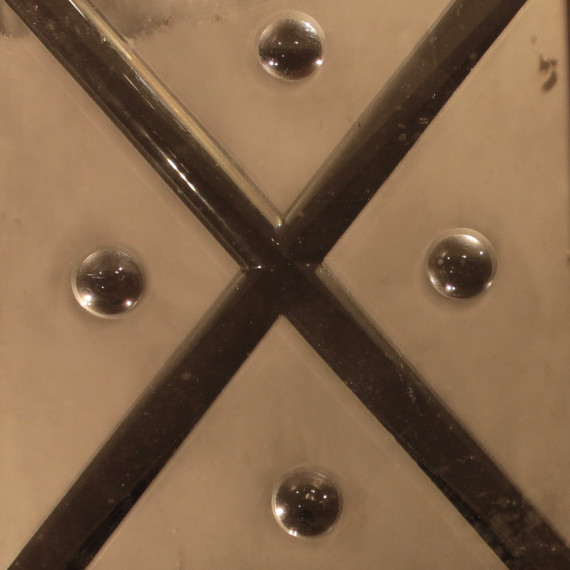

The most important piece of equipment in a silvering workshop was the silvering table. Tin foil was laid out on this table and smoothed out. Then, mercury was poured over it. The silverer slid the cleaned sheet of glass onto the mercury layer, then tilted the table so that the excess mercury could drain away. Held down with weights, the mirror then had to rest in a horizontal position until the tin-mercury amalgam adhered firmly to the plate glass.

Due to the ubiquity of mercury in the workplace, 'mercurial diseases' were widespread among silvering workers. This form of chronic poisoning manifested itself in sensory and speech disorders, as well as limb tremors – the 'tremor mercurialis', and could be fatal. However, after several weeks, patients often recovered to the extent that they were fit to work again.

Wet silvering was developed around the middle of the 19th century as an alternative to mercury silvering. Employing this process successfully since 1859, Erlangen's mirror factory also contributed pioneering work in this field. Silver-based silvering only became dominant, however, due to pressure from occupational health and safety regulations introduced in 1889.

< Previous chapter | Next chapter >